I very much enjoy this book and its place in the series, both for doing what only a series like this can do and for having a surprisingly profound thematic core.

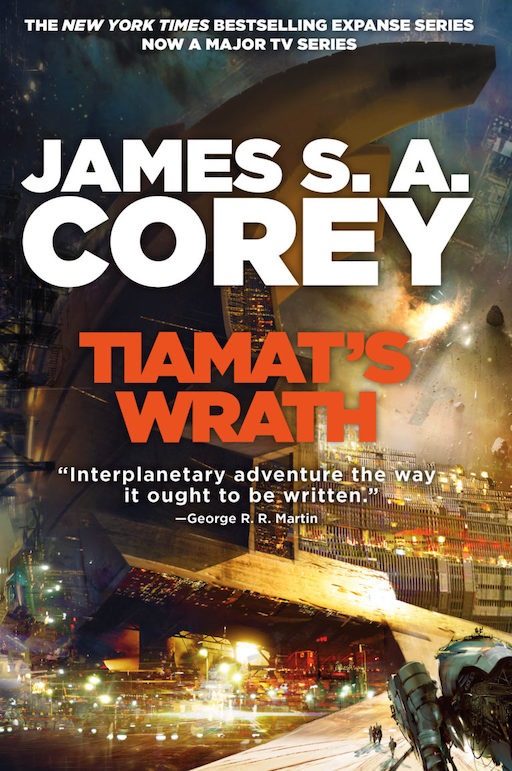

I reread Tiamat’s Wrath — the 8th and penultimate novel in James S. A. Corey’s sci-fi series The Expanse — this week, after having reread the first seven books while down with the flu over my Christmas vacation and in the weeks since. I enjoyed it just as much the second time through as I did the first, and I’m eager to see how the final installment plays out when it arrives sometime this year.

(Normally I would be nervous about a final installment in such a long series. Here… well, I’m still a little nervous whether the last book will stick the landing, but the authors whose joint pen name is James S. A. Corey have done such a good job that I’m more confident than I would normally be.)

On this read-through, a couple things caught my attention — little notes about the way the world is built and the story told that I hadn’t noticed on previous reads.

Minor spoilers for the series up through Tiamat’s Wrath follow, inevitably. Don’t read this if you want to read the series and don’t want to be spoiled.

Also: I enjoy these books, but I don’t unambiguously recommend them. There is considerable violence, some of it gory, and a lot of language, and a number of fade-to-black-style sexual encounters and a good many more casual references to sex. Caveat lector.

What books like this can do

The first of those notes is the way the eighth book in a series can do things that no other kind of book really can. Characters can have payoffs at the end of thousands and thousands of pages that even the best single volume can never really match. This is one of the great allures of epic fantasy and sci-fi: it tells stories on scopes — scopes not only of the world but of characters — that few other genres even reach for. The closest parallels I can think of are popular thriller or mystery series with long-running heroes, but even they aren’t doing quite the same thing that epic fantasy or sci-fi are. In particular, they rarely let main characters die, at least in the books outside sci-fi that I’m acquainted with. (Mild spoilers: this book does that!)

This is part of the appeal of the Marvel movies of the last decade and change, as well as every long-running television series ever (but especially the good ones with an eye to both character and plot development). Watching Iron Man and Captain America over the course of a decade — ridiculous though the ideas were at times — lent an emotional potency to Endgame that few other movies of its genre (blockbuster action movies) could hope to muster.

Epic sci-fi and fantasy aren’t necessarily the richest fiction I read.1 They can do things that most other genres don’t do, though, even if they could, and I value them for that.

One big idea

The Expanse novels are not in the least message books — they’re just aiming to be, and succeeding at being, really good space opera. They do, however, have a consistent idea that runs through the whole series. Namely: that violence may sometimes be necessary, but that doesn’t make it good or right, and those who are forced to fight by others who leave no other choice should always fight toward reconciliation, not merely victory.

That this would be such a pervasive theme might seem a bit ironic: the series tells the story of several wars, of varying degrees of nastiness. But the authors have been consistent. They have shown a world where war is always a bad thing, not to be taken up lightly or happily, and fought only in pursuit of peace. Not peace at the barrel of a gun, but the peace of people no longer enemies with each other.

This little exchange, three quarters of the way through Tiamat’s Wrath, captures the sentiment clearly and beautifully:

“I don’t want to fight. I don’t want anyone to get hurt. Or die. Not our side, and not them either. I want to reconcile. That’s why Bobbie always got so frustrated with me. She wanted to win.”

“Looks like you do too, now.”

“The problem is it’s hard to reconcile when you’ve lost,” Naomi said. “Someone takes all the power, and you try to bring them into the fold again? That’s capitulation. I don’t think violence solves anything, not even this. Not even now. But maybe winning puts us in a place that we can be gracious.”

“Meet Duarte halfway?” Alex said. She could hear in his voice that he wasn’t convinced. If she couldn’t sway him, maybe there wasn’t hope. But she tried.

“Make space for him. Maybe he’ll take it, maybe he won’t. Maybe his admirals will see something in it he doesn’t. The point of this fight isn’t to kill Laconia. It’s to get enough power that we can close the distance they opened between them and everyone else. That may mean punishing some people. It may mean answering for old crimes. But it has to mean finding some way forward.”

That framing — fighting only when it is truly necessary, and aiming not to “win” in the sense of beating the other people down into submission but only to bring them to the table — is too rare in our world. I’m grateful that this series has painted a world where those are the good guys, and sometimes they do win, and what comes out of the kindness of their victories is something still imperfect, but better than what came before.

What a lovely thematic line for this low-brow,2 high-concept space opera to hold.

Tolkien excepted. Obviously. ↩︎

I’ve seen this done this well in this kind of low-brow art only one other place: Doctor Who. ↩︎